Code

Six ways to hone the message of a data visualization.

At this point in the course, you have a bevy of different types of statistical graphics under your belt: scatterplots, histograms, dot plots, violin plots, box plots, density curves, and bar plots of several kinds. You also have a broad framework to explain how these graphics are composed: the Grammar of Graphics. But to what purpose? Why plot data? For whom?

Every time you build a plot, you do so with one of two audiences in mind.

The process of building understanding from a data set is one that should be driven by curiosity, skepticism, and thoughtfulness. As a data scientist, you’ll find yourself in conversation with your data: asking questions of it, probing it for structure, and seeing how it responds. This thoughtful conversation is called exploratory data analysis (or EDA).

During EDA, the aim is to uncover the shape and structure of your data and to uncover unexpected features. It’s an informal iterative process where you are your own audience. In this setting, you should construct graphics that work best for you.

At some point, you’ll find yourself confident in the claim that can be supported by your data and the focus changes to communicating that claim as effectively as possible with a graphic. Here, your audience shifts from yourself to someone else: other scientists, customers, co-workers in a different part of your company, or casual readers. You must consider the context in which they’ll be viewing your graphic: what they know, what they expect, what they want.

In these notes we discuss six ways to hone the message of your data visualization. They are:

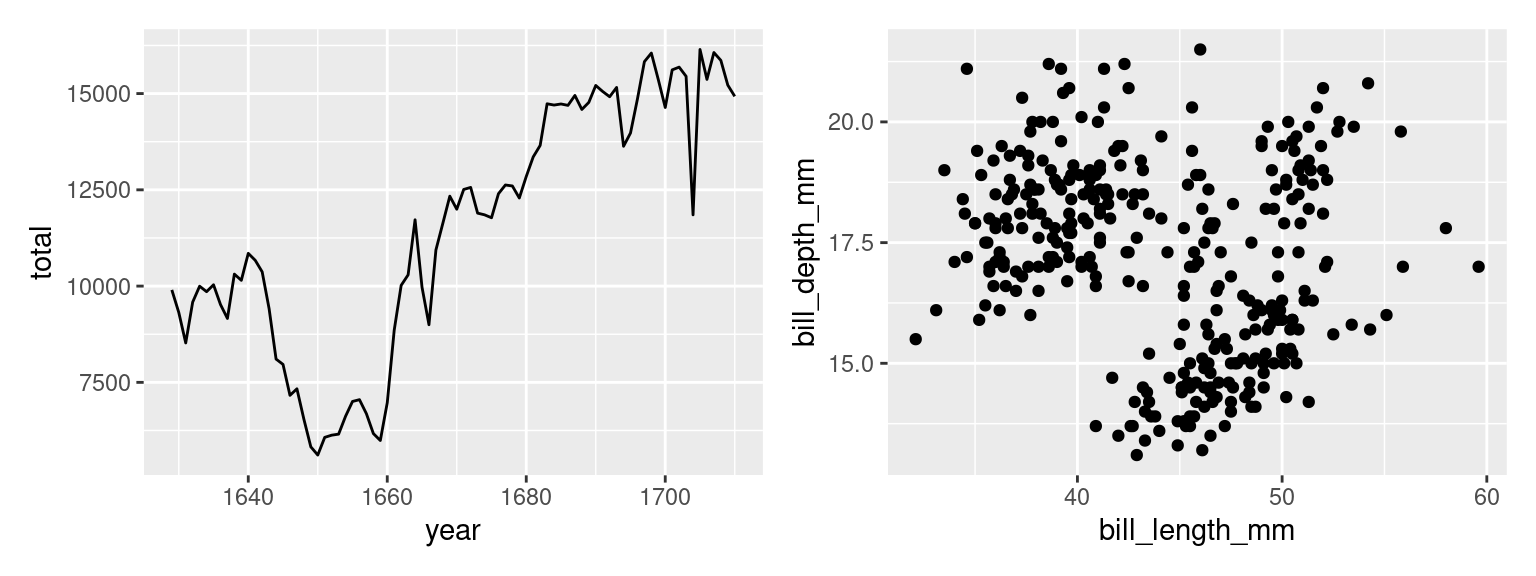

We will use two running examples throughout these notes: a line plot of the number of christenings in 17th century London1 and a scatter plot showing the bill sizes of penguins near Palmer Station, Antarctica2.

Once you have your first draft of a plot complete and you’re thinking about how to fine tune it for your audience, your eye will turn to the aesthetic attributes. Is that color right? What about the size of the points?

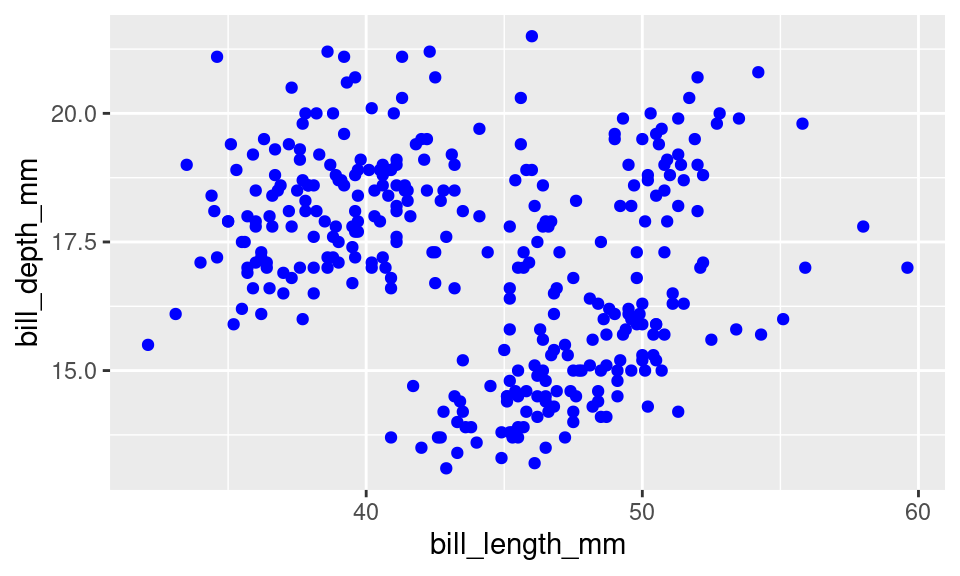

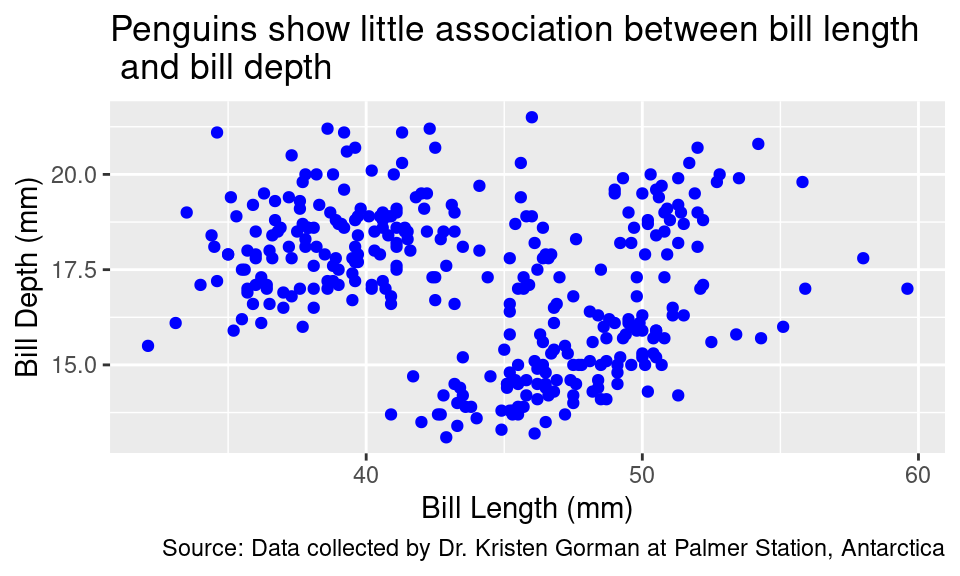

Consider the first draft of the penguins plot above. It might feel a bit drab to have a large mass of points all in black, the same color as the labels and surrounding text. Let’s make the points blue instead to make them stand out a bit more.

ggplot(penguins, aes(x = bill_length_mm,

y = bill_depth_mm,

color = "blue")) +

geom_point()

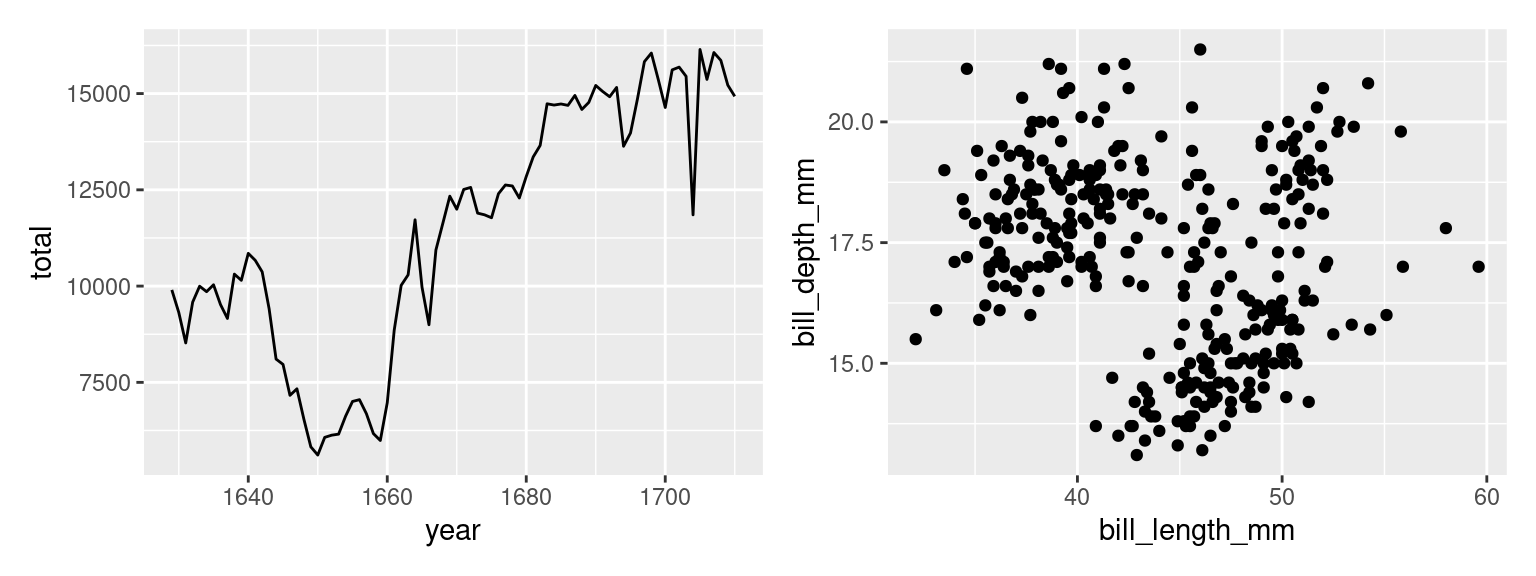

This is . . . unexpected. Why did it color the points red? Is this a bug?

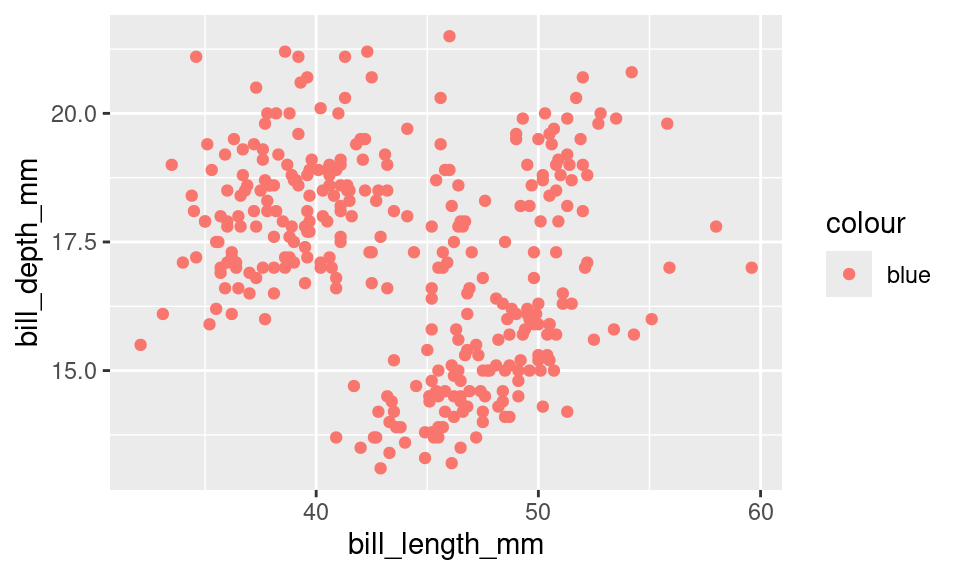

What we’ve stumbled into is a subtle but essential distinction in the grammar of graphics: mapping vs setting. When you put an aesthetic attribute (x, color, size, etc.) into the aes() function, you’re mapping that attribute in the plot to whatever data lives in the corresponding column in the data frame. Mapping was this process:

That’s not what we set out to do here. We just wanted to tweak the look of our aesthetic attributes in a way that doesn’t have anything to do with the data in our data frame. This process is called setting the attribute.

To set the color to blue3, we need to make just a small change to the syntax. Let’s move the color = "blue" argument outside of the aes() function and into the geom_() function.

ggplot(penguins, aes(x = bill_length_mm,

y = bill_depth_mm)) +

geom_point(color = "blue")

Ah, that looks much better!

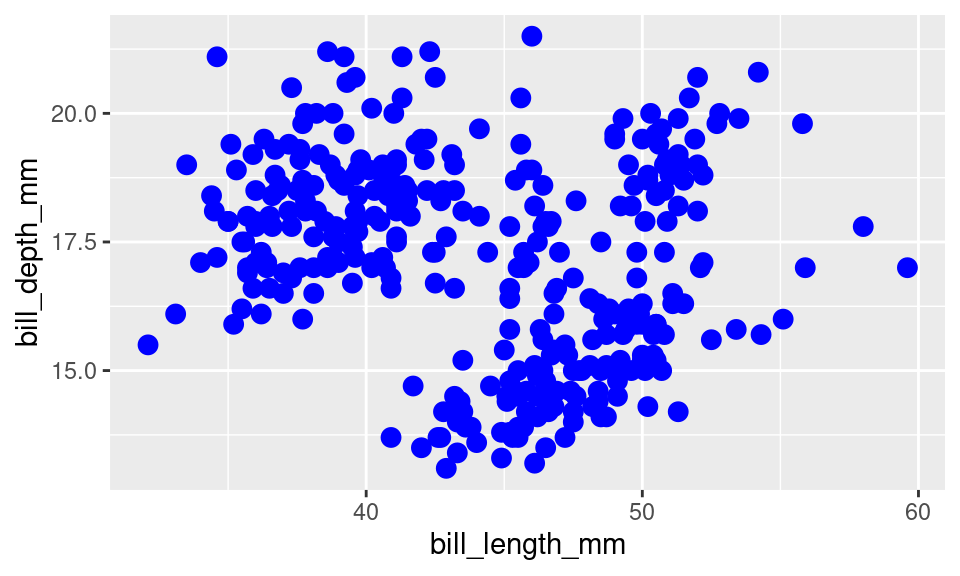

Color isn’t the only aesthetic attribute that you can set. Let’s increase slightly the size of our points by setting the size to three times the size of the default.

ggplot(penguins, aes(x = bill_length_mm,

y = bill_depth_mm)) +

geom_point(color = "blue", size = 3)

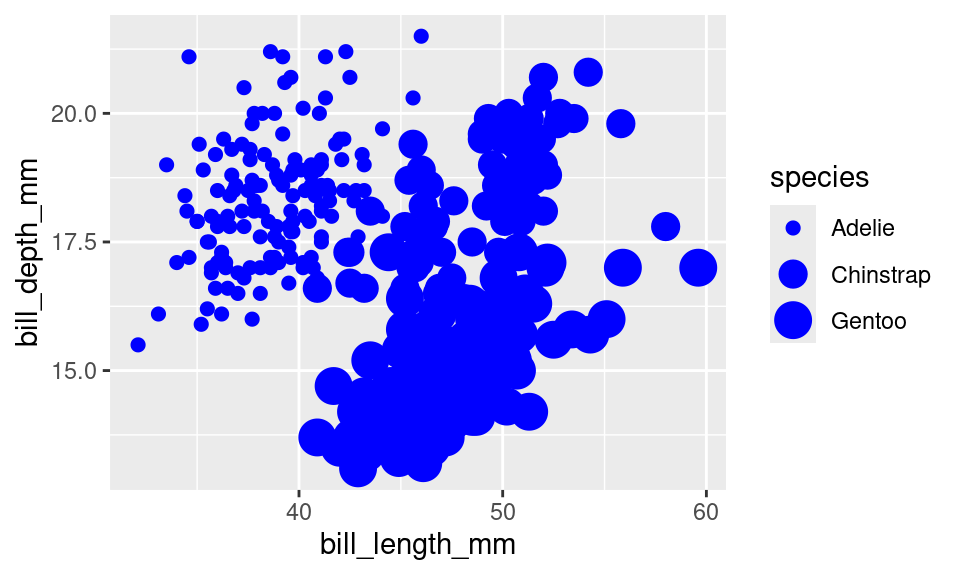

It’s not clear that that improves the readability of the plot - there is more overlap between the points now - but the setting worked. How would it have looked if instead we had mapped the size? When you map, you need a map to a column in your data frame, so let’s map size to species.

ggplot(penguins, aes(x = bill_length_mm,

y = bill_depth_mm,

size = species)) +

geom_point(color = "blue")

We’ve made a mess of our plot now, but it is clear what happened. R looked inside the species column, found a categorical variable with three levels and selected a distinct size for each of those levels.

This is another area in which the grammar of graphic guides clear thinking when constructing a graphic. The aesthetic attributes of a plot can be determined either by variability found in a data set or by fixed values that we set. The former is present in all data visualization but it’s the latter that comes into play when fine-tuning your plot for an audience.

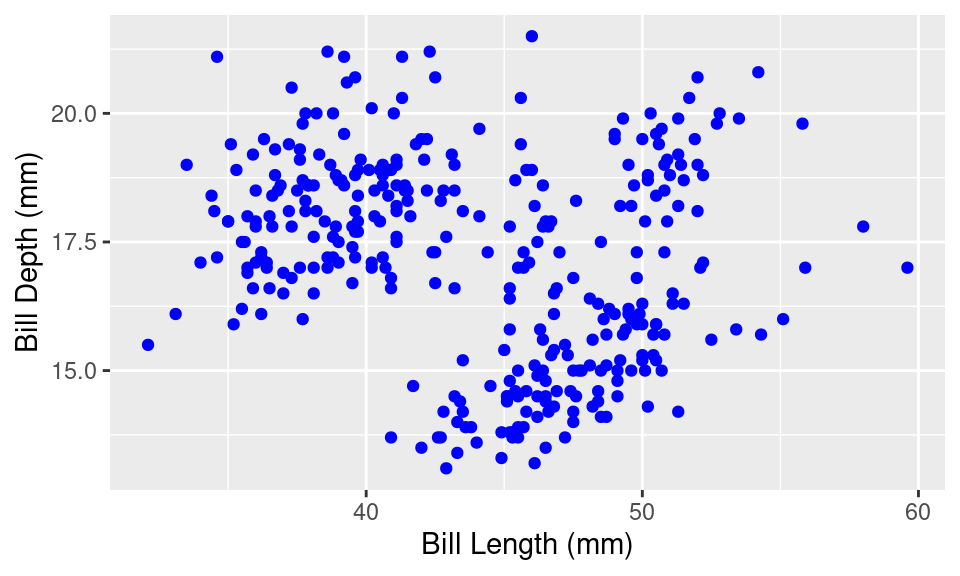

You may have noticed that ggplot2 pulls the labels for the x-axis, the y-axis, and the legend directly from the names of the variables in the data frame. This results in labels like bill_length_mm, which is no problem when you’re making plots for yourself - you know what this variable means. But will an outside audience?

You can change the labels of your plot by adding a labs() layer.

ggplot(penguins, aes(x = bill_length_mm,

y = bill_depth_mm)) +

geom_point(color = "blue") +

labs(x = "Bill Length (mm)",

y = "Bill Depth (mm)")

Axis and legend labels should be concise and often include the units of measurement. If you find them getting too wordy, know that you can clarify or expand on what is being plotted either in a figure caption or in the accompanying text.

Speaking of captions, those a can be added too, as well as a title.

ggplot(penguins, aes(x = bill_length_mm,

y = bill_depth_mm)) +

geom_point(color = "blue") +

labs(x = "Bill Length (mm)",

y = "Bill Depth (mm)",

title = "Penguins show little association between bill length\n and bill depth",

caption = "Source: Data collected by Dr. Kristen Gorman at Palmer Station, Antarctica")

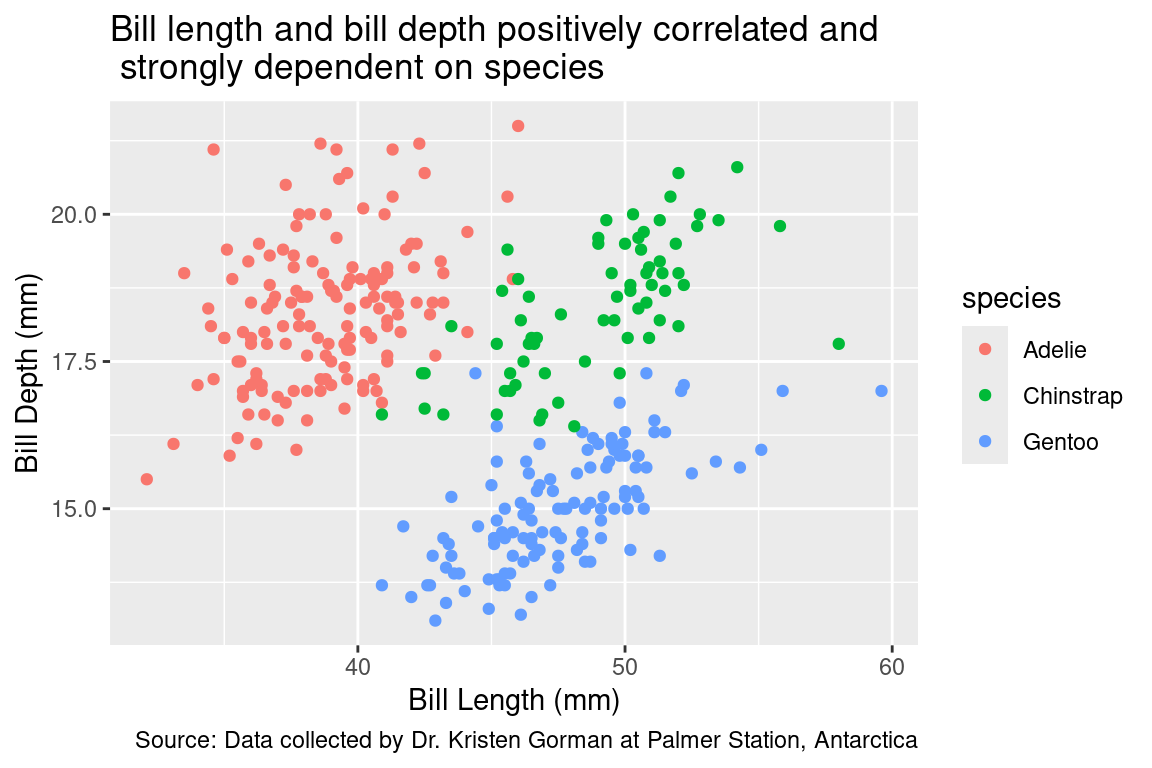

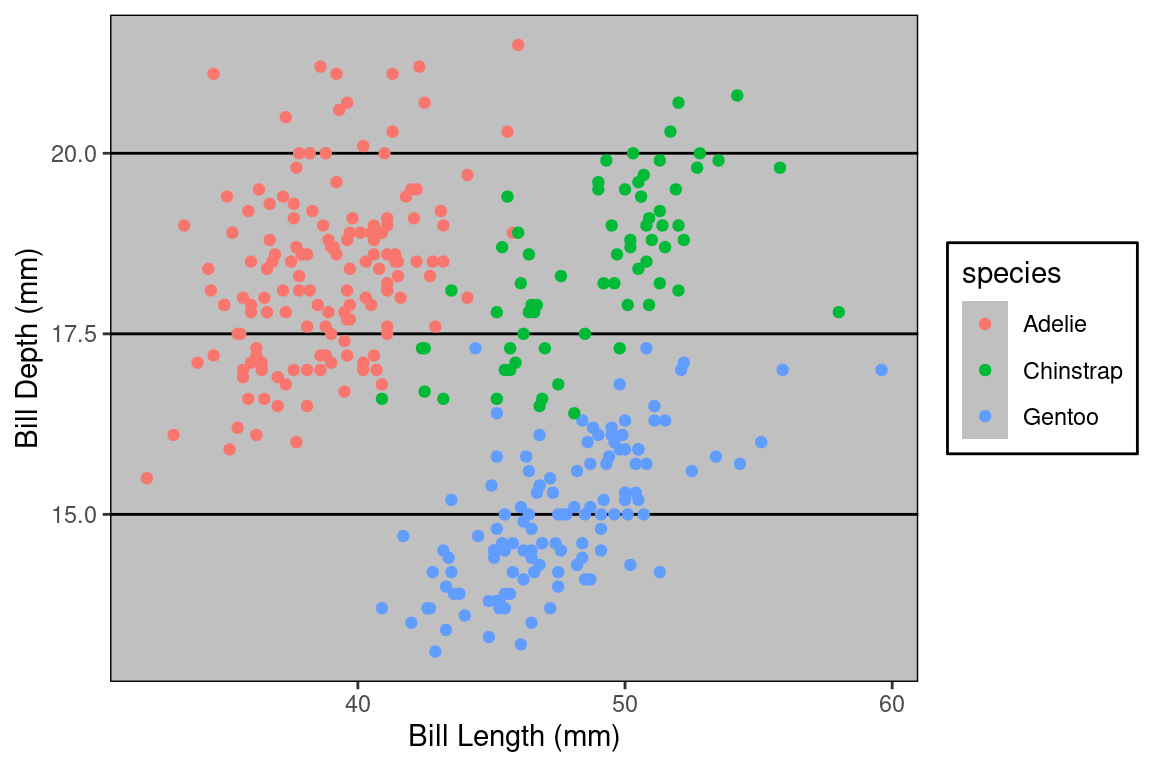

The title of a plot is valuable real estate for communicating the primary story of your plot. It should highlight the most important structure in the data. In the plot above, there appears to be little correspondence between bill length and bill depth. Of course, that changes when we map species to color. Let’s make that plot and title it accordingly.

ggplot(penguins, aes(x = bill_length_mm,

y = bill_depth_mm,

color = species)) +

geom_point() +

labs(x = "Bill Length (mm)",

y = "Bill Depth (mm)",

title = "Bill length and bill depth positively correlated and\n strongly dependent on species",

caption = "Source: Data collected by Dr. Kristen Gorman at Palmer Station, Antarctica")

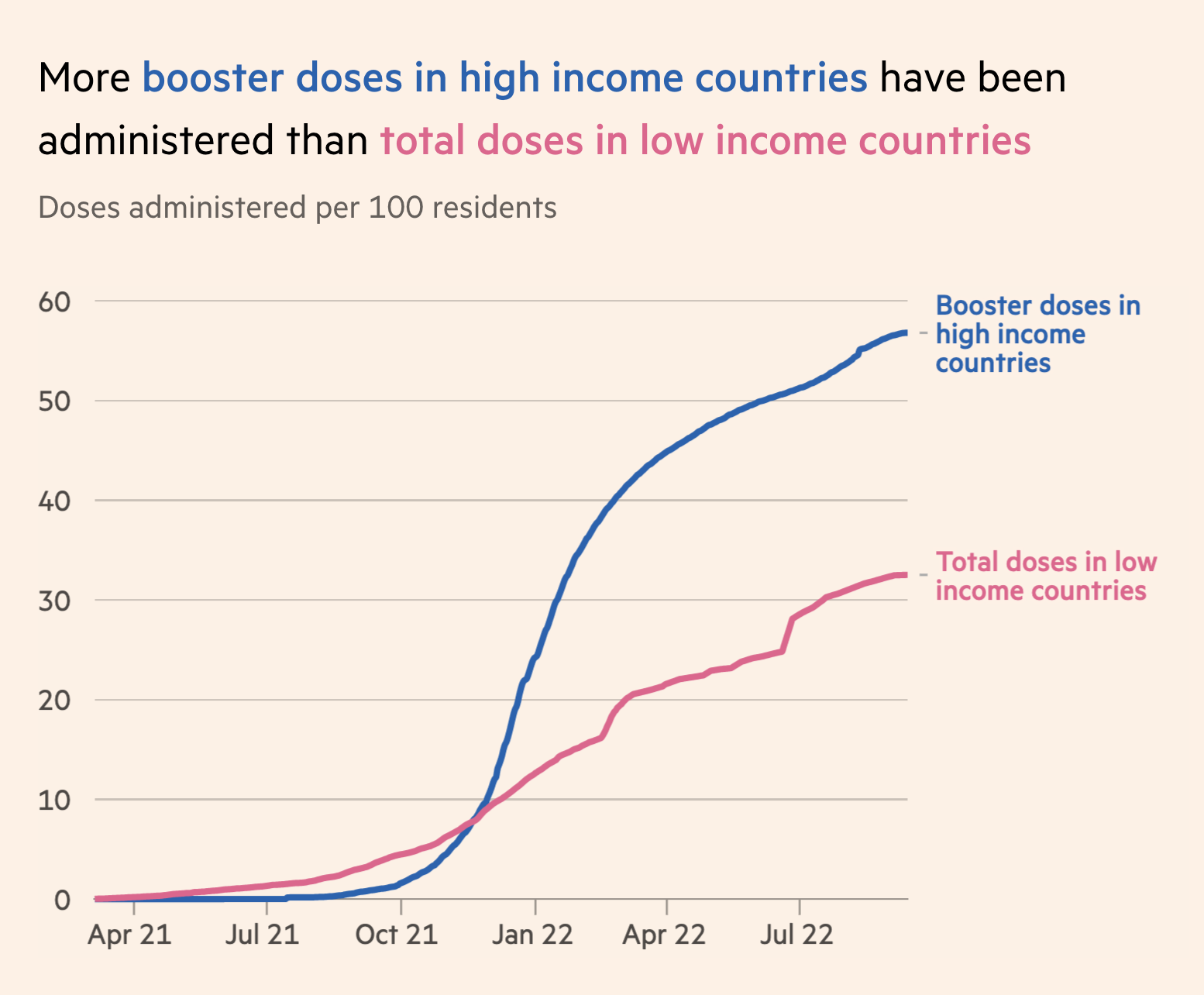

The practice of using the plot title to convey the main message of the plot is used to powerful effect by the visualization experts at the British publication, The Financial Times4. They have developed a wealth of visualizations to help readers understand what is happening with public health throughout the pandemic. The sobering graphic below uses the title to guide the viewer to the most important visual structure in the plot: the yawning vertical gap between dosage rates between high and low income countries.

When a person views your plot, their first impression will be determined by a coarse interpretation of the boldest visual statement. When using a line plot, that is usually the general trend seen when reading left to right.

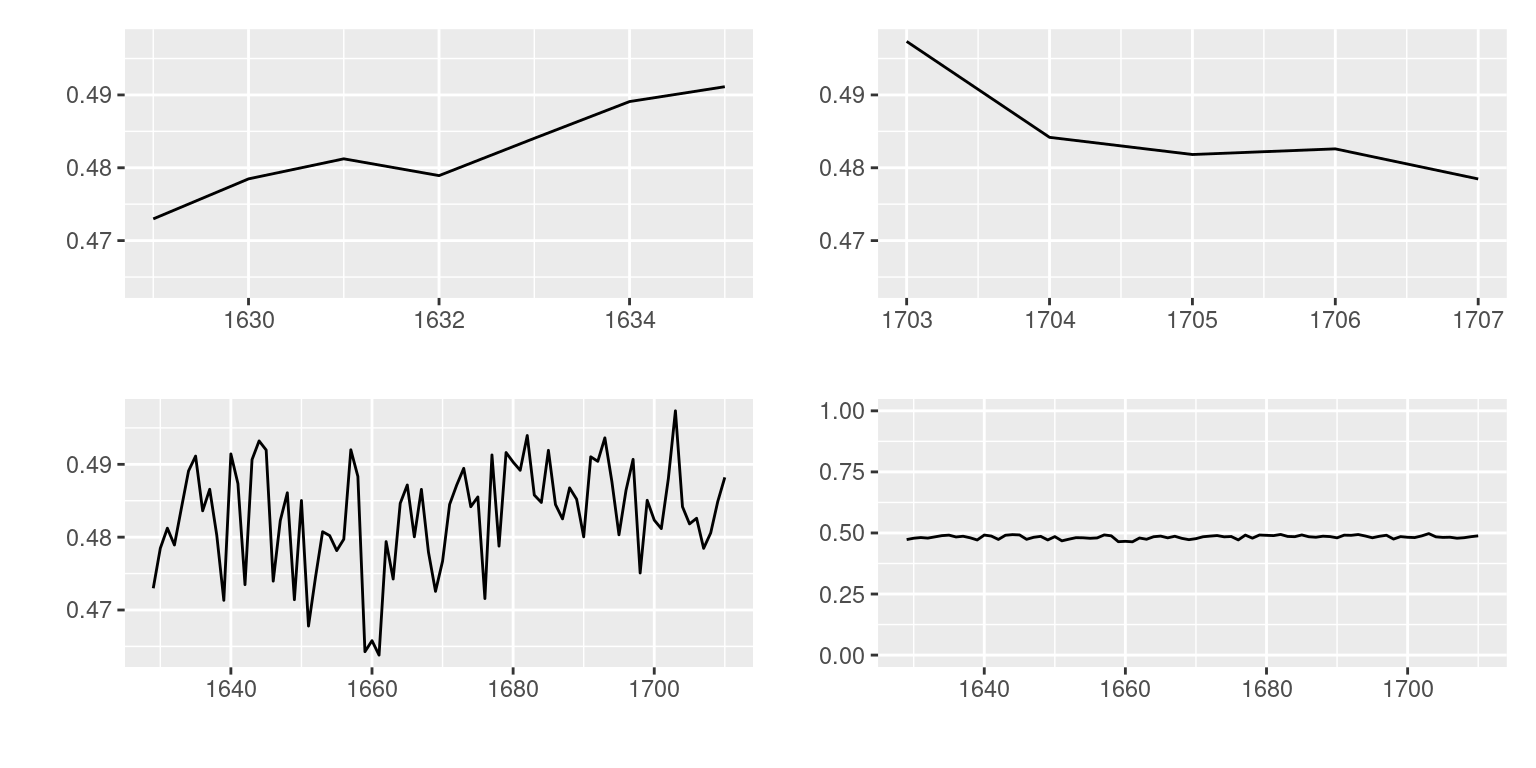

What is the first word that comes to mind to describe the trend in each of the four plots below?

arbuthnot <- mutate(arbuthnot, p_girls = girls / total)

p1 <- ggplot(arbuthnot, aes(x = year,

y = p_girls)) +

geom_line() +

xlim(1629, 1635) +

labs(x = "", y = "")

p2 <- ggplot(arbuthnot, aes(x = year,

y = p_girls)) +

geom_line() +

xlim(1703, 1707) +

labs(x = "", y = "")

p3 <- ggplot(arbuthnot, aes(x = year,

y = p_girls)) +

geom_line() +

labs(x = "", y = "")

p4 <- ggplot(arbuthnot, aes(x = year,

y = p_girls)) +

geom_line() +

ylim(0, 1) +

labs(x = "", y = "")

(p1 + p2) / (p3 + p4)

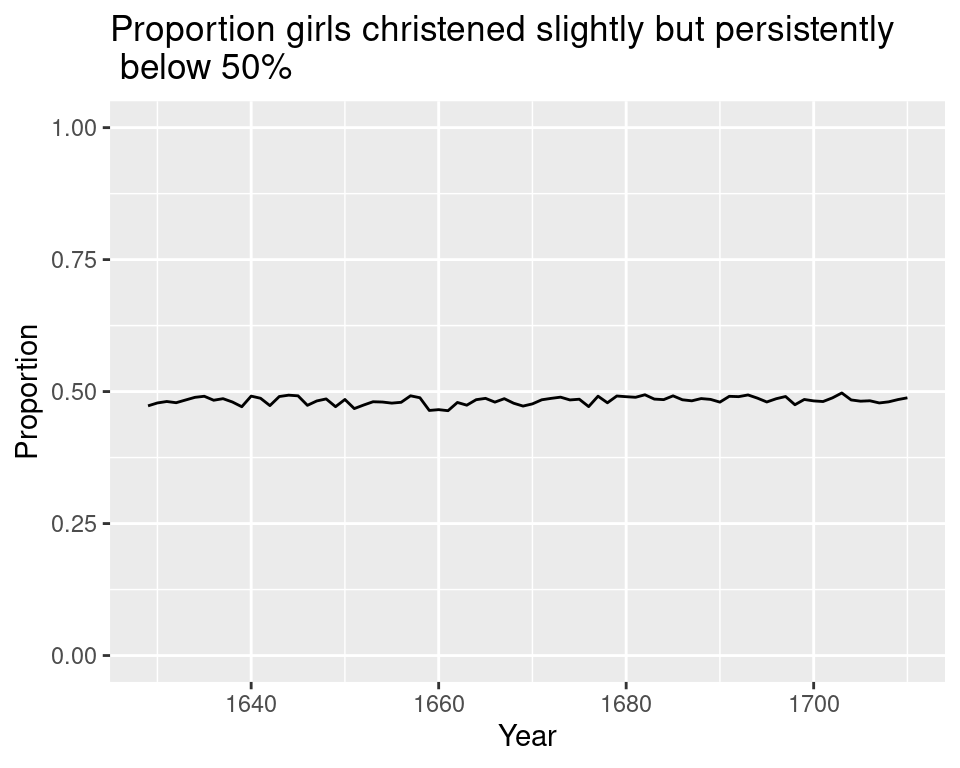

Clockwise from the upper left, you likely said something like “increasing”, “decreasing”, “variable”, and “stable”. Now take a second look. What exactly is being plotted here?

The labels along the axes are a hint to what you’re looking at here. These are, in fact, four plots from the exact same data: Arbuthnot christening records, with the proportion of girls christened on the x-axis. What differs is the limits of the x- and y-axes.

Most software will automatically set the limits of your plot based on the range of the data. In the Arbuthnot data, the years range from 1629 to 1710 and the proportion of girls christened ranges from .463 to .497. The leads to the default graphic found in the lower left panel. Each of the other three plots have modified the limits of the x- or y-axis to capture different parts the data scaled in different ways. In ggplot2 this is done by adding an xlim() or ylim() layer.

This is the power of scaling. From one data set, you can convey four different (and incompatible!) messages by changing the scale. So which one is correct? It depends on the context and the question that drove the collection of the data. John Arbuthnot sought to understand the whether the chance of being born a girl is 1/2. That question is answered most clearly by the following plot (with the title driving home that main message).

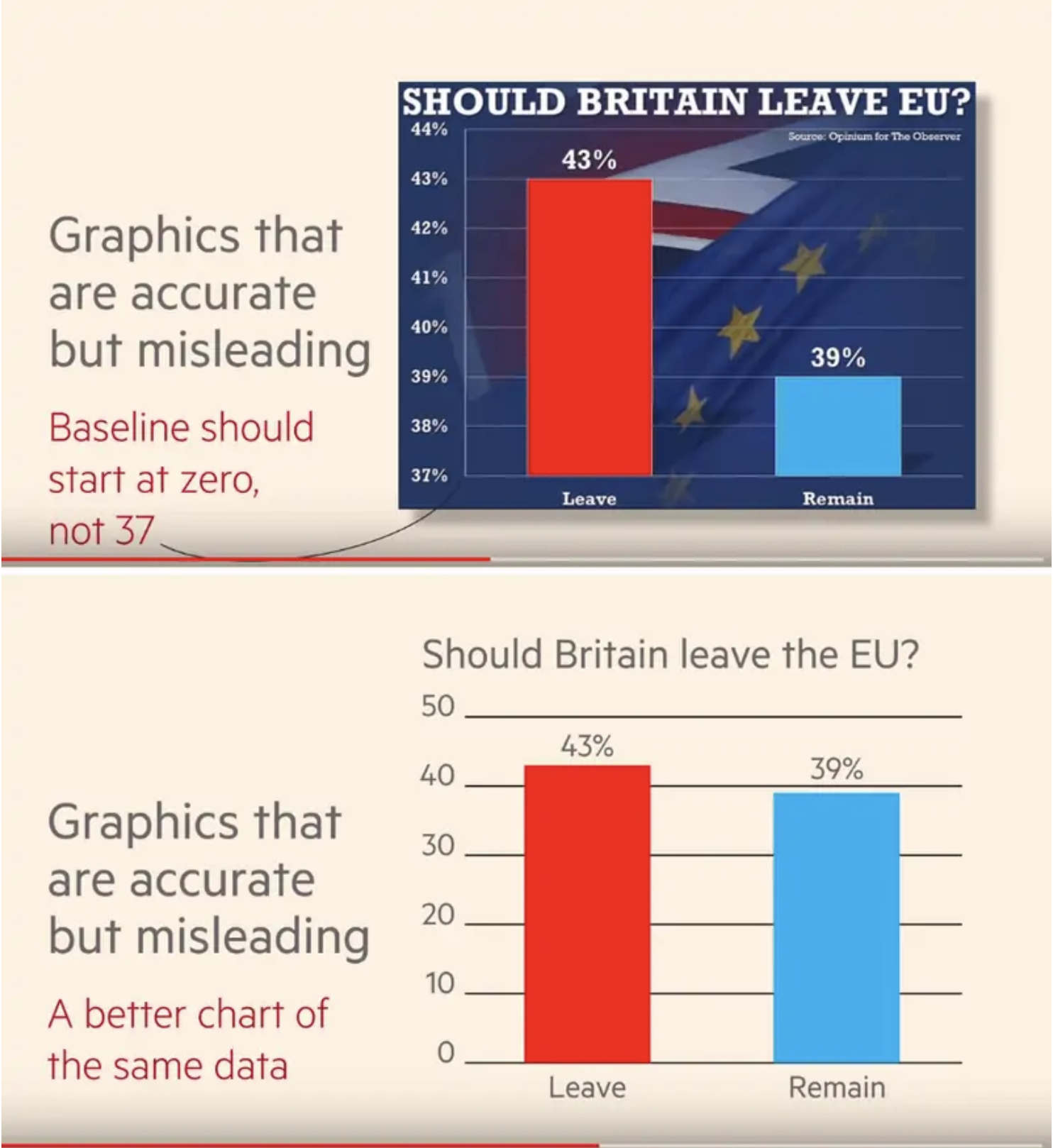

The importance of scale extends beyond scatter and line plots. Barcharts are often the subject of careful scaling to convey a particular message. What do you think the goal was of the creator of the plot titled “Should Britain Leave EU?”5

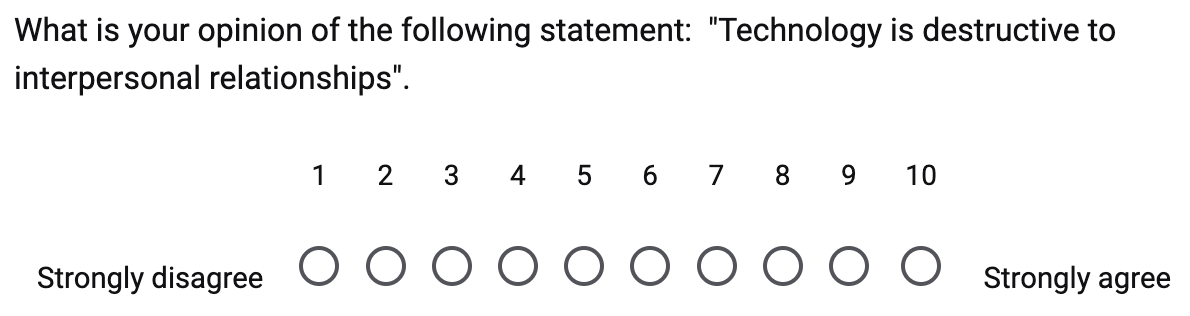

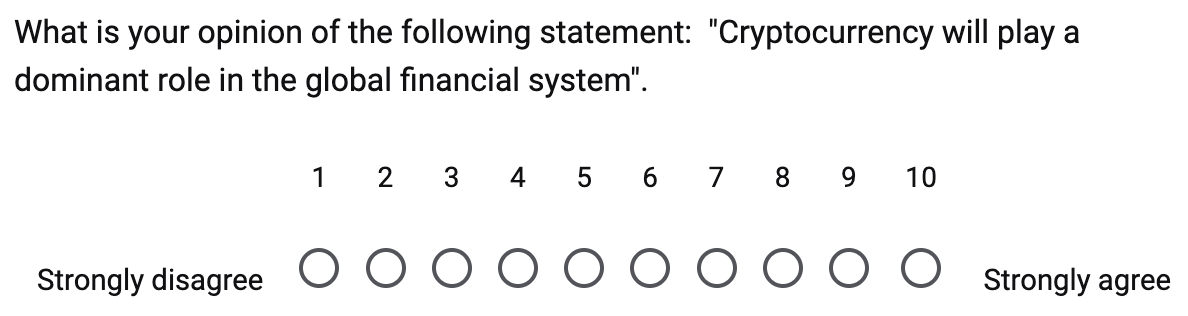

Introductory statistics students filled out a survey that asked them their opinion on several topics including:

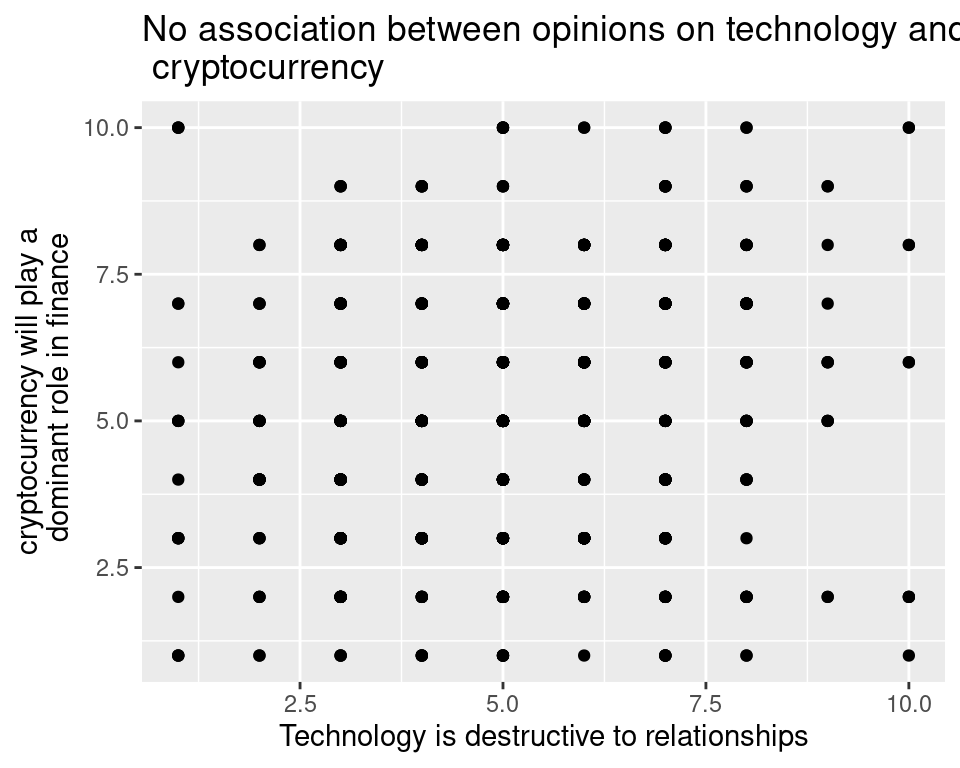

The result was a data frame with 707 rows (one for every respondent) and 2 columns of discrete numerical data. A natural way to visualize this data is by creating a scatter plot.

ggplot(class_survey, aes(x = tech,

y = crypto)) +

geom_point() +

labs(x = "Technology is destructive to relationships",

y = "cryptocurrency will play a\n dominant role in finance",

title = "No association between opinions on technology and \n cryptocurrency")

The eye is immediately drawn to the eerie geometric regularity of this data. Isn’t real data messier than this? What’s going on?

A hint is in the sample size. The number of observations in the data set was over 600 and yet the number of points shown here is just a bit under 100. Where did those other observations go?

It turns out they are in this plot, they’re just piled on on top of the other. Since there are only 10 possible values for each question, many students ended up selecting the same values for both, leading their points to be drawn on top of one another.

This phenomenon is called overplotting and it is very common in large data sets. There are several strategies for dealing with it, but here we cover two of them.

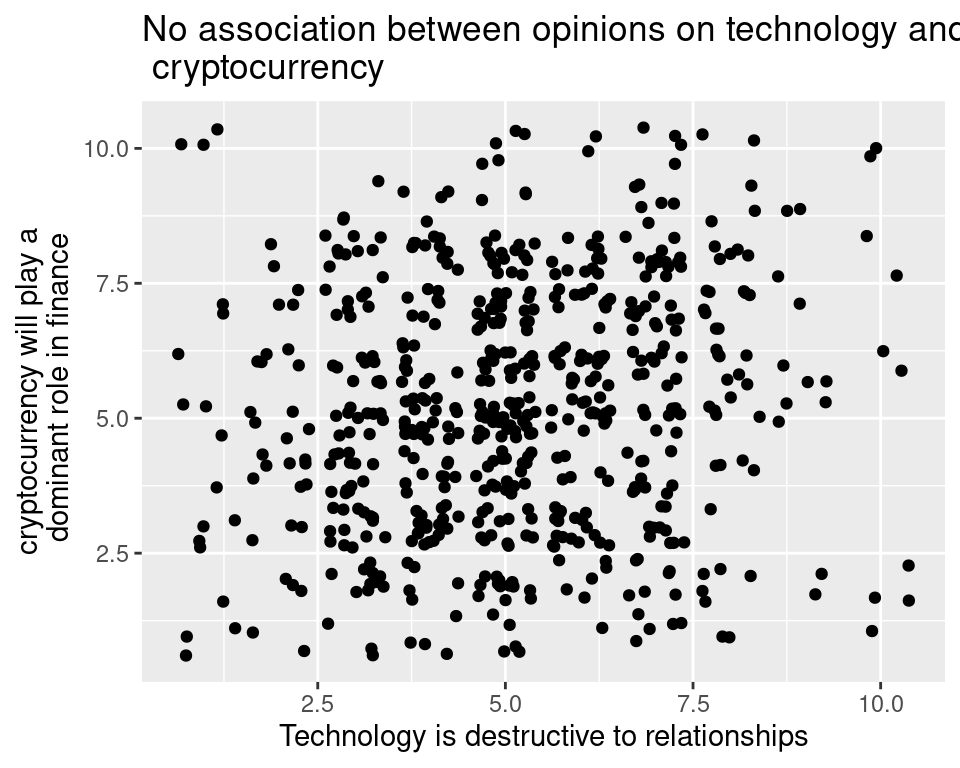

One approach to fixing the problem of points piled on top of one another is to unpile them by adding just a little bit of random noise to their x- and y-coordinate. This technique is called jittering and can be done in ggplot2 by replacing geom_point() with geom_jitter().

set.seed(20)

ggplot(class_survey, aes(x = tech,

y = crypto)) +

geom_jitter() +

labs(x = "Technology is destructive to relationships",

y = "cryptocurrency will play a\n dominant role in finance",

title = "No association between opinions on technology and \n cryptocurrency")

Ahh . . . there are those previously hidden students. Interestingly, the title on the first plot still holds true: even when we’re looking at all of the students, there doesn’t appear to be much of a pattern. There is certainly not the case in all overplotted data sets! Often overplotting will obscure a pattern that jumps out after the overplotting has been attended to.

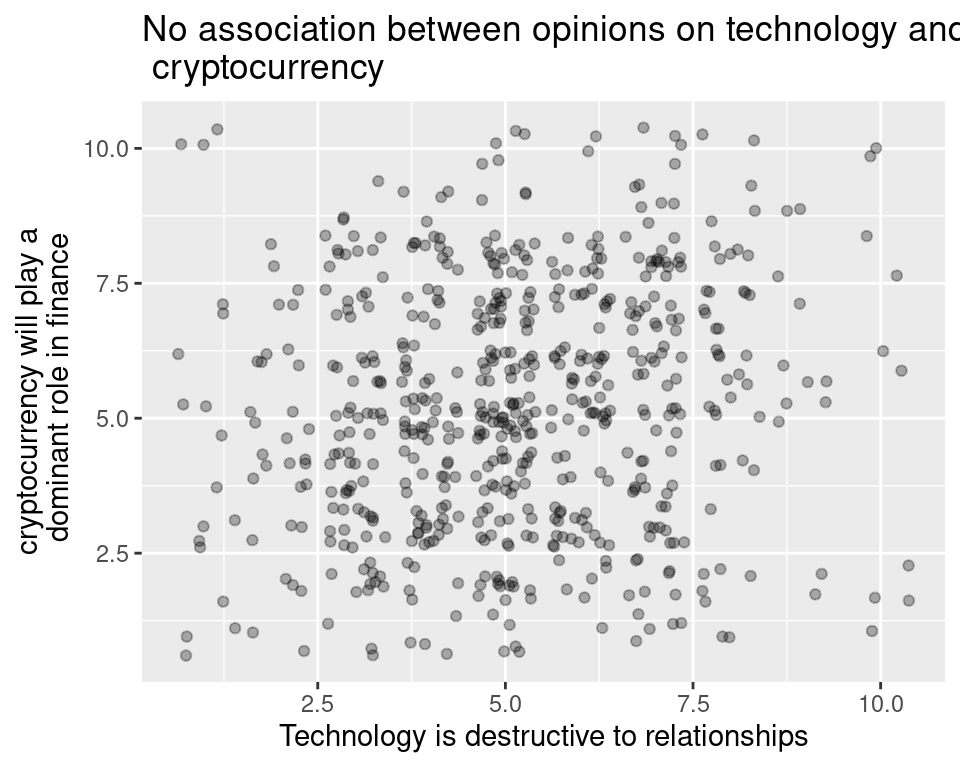

The second technique is to make the points transparent by changing an aestheric attribute called the alpha value. Let’s combine tranparency with jittering to understand the effect.

set.seed(20)

ggplot(class_survey, aes(x = tech,

y = crypto)) +

geom_jitter(alpha = .3) +

labs(x = "Technology is destructive to relationships",

y = "cryptocurrency will play a\n dominant role in finance",

title = "No association between opinions on technology and \n cryptocurrency")

Alpha is a number between 0 and 1, where 1 is fully opaque and 0 is fully see-through. Here, alpha = .3, which changes all observations from black to gray. Where the points overlap, their alpha values add to create a dark blob.

There’s still no sign of a strong association between these variables, but at least, by taking overplotting into consideration, we’ve made that determination after incorporating all of the data.

What piece of software did I use to produce the following plot?

library(ggthemes)

ggplot(penguins, aes(x = bill_length_mm,

y = bill_depth_mm,

color = species)) +

geom_point() +

labs(x = "Bill Length (mm)",

y = "Bill Depth (mm)") +

theme_excel()

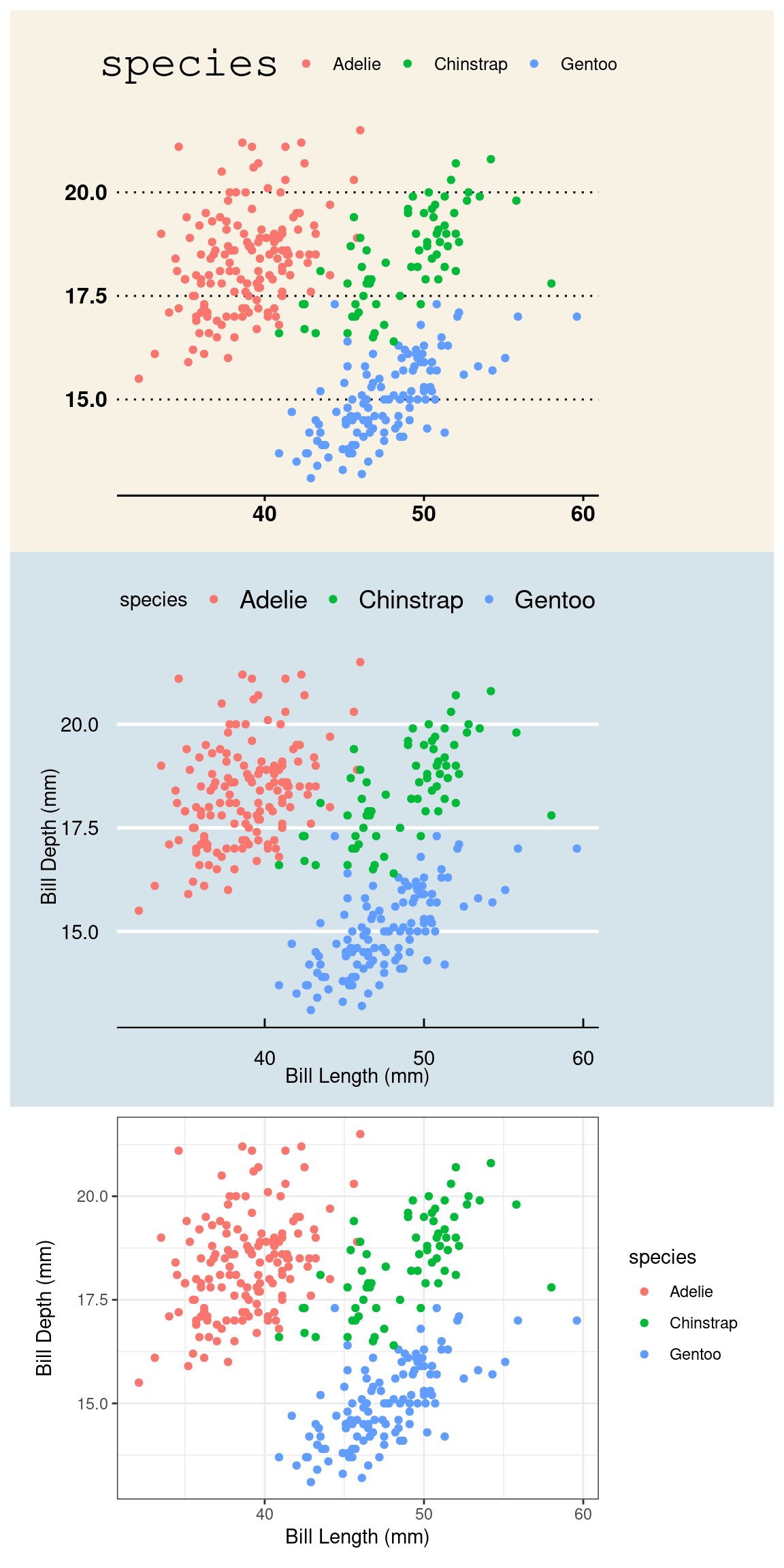

If you said “Excel”, you are correct! Well… it is Excel in spirit. What makes this plot look like it was made in Excel are a series of small visual choices that were made: the background is a dark gray, there are black horizontal guide lines, and the plot and the legend is surrounded by a black box. Small decisions like these that effect the overall look and feel of the plot are called the theme.

Let’s look at a few more. Do they look familiar?

p1 <- ggplot(penguins, aes(x = bill_length_mm,

y = bill_depth_mm,

color = species)) +

geom_point() +

labs(x = "Bill Length (mm)",

y = "Bill Depth (mm)") +

theme_wsj()

p2 <- ggplot(penguins, aes(x = bill_length_mm,

y = bill_depth_mm,

color = species)) +

geom_point() +

labs(x = "Bill Length (mm)",

y = "Bill Depth (mm)") +

theme_bw()

p3 <- ggplot(penguins, aes(x = bill_length_mm,

y = bill_depth_mm,

color = species)) +

geom_point() +

labs(x = "Bill Length (mm)",

y = "Bill Depth (mm)") +

theme_economist()

p1 / p3 / p2

They are, from top to bottom, a theme based on The Wall Street Journal, The Economist, and one of the themes built into ggplot2 packaged called bw for “black and white” (there are no grays). The ggplot2 library has several themes to choose from and yet more live in other packages like ggthemes. To use a theme, all you need to do is add a layer called theme_NAME (e.g. for the black and white theme, use theme_bw).

Themeing your plots is an easy way to change the look of your plot. Tinker with a few different themes and considering adding them to your labs6. But, as with all design decisions around graphics, be sure to think about your audience. You might find the Excel aesthetics ugly and dated, but will your audience? If you’re presenting your plot to a community that works with Excel plots day in and day out, that’s probably a sound choice. If you are preparing a plot for submission to a scientific journal, a more minimalist theme is more appropriate.

In the same way that a title highlights the main message of a plot, you can rely upon visual cues to draw attention to certain components or provide helpful context.

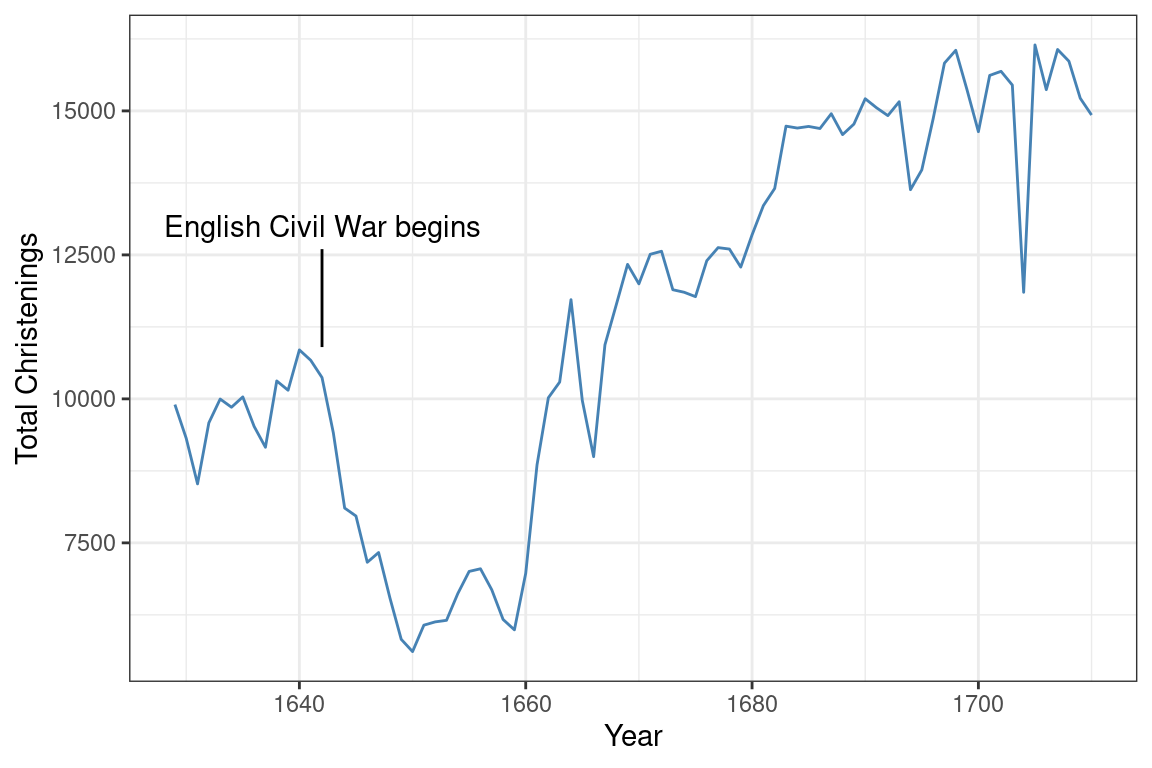

The christening records collected by John Arbuthnot, although they seem like a very simple data set, actually capture a wealth of historical information. We can add this information to our plot by adding annotations.

Were you curious about what caused that dip in the number of christenings in 17th century London? It happens to correspond to the duration of the English Civil War, when the monarchy was overthrown by a dictator named Oliver Cromwell. This very important context can be conveyed by adding a text label and a line segment through two new annotate() layers.

Within ggplot2, annotations are a flexible way to add the context or comparisons that help guide readers in interpreting your data. You can add text, shapes, lines, points. To learn more, consult the documentation7.

So if the drop after 1642 corresponds to the English Civil War, what about the spike down around 1666? What about 1703? If you’re curious, explore Wikipedia to find out and add those events as annotations to this plot.

There are two main uses for data visualization. The first is as part of exploratory data analysis, when you are constructing plots for yourself to better understand the structure of the data. When you’re ready to communicate with an outside audience using graphics, more thought is needed: you must think about the difference between mapping and setting, the use of labels for clarity, the importance of scale, overplotting, themes, and annotations.

This is far from a complete list of what all can be done to improve your plots, but it is sufficient to produce polished graphics that effectively communicate your message.

For data documentation, see the stat20data R package.↩︎

For data documentation, see the palmerpenguins R package.↩︎

To see the vast (and somewhat strange) palette of color names that R knows, type colors() at the console.↩︎

Visualization drawn from the excellent collection of graphics at the Financial Times Covid Tracker https://ig.ft.com/coronavirus-vaccine-tracker/.↩︎

Graphics from the keynote of John Burn-Murdoch at rstudio::conf() 2021.↩︎

Explore the themes available within ggplot2 by reading the documentation https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org/reference/ggtheme.html. For the additional themes held in the ggthemes package, read this: https://yutannihilation.github.io/allYourFigureAreBelongToUs/ggthemes/.↩︎

Documentation for annotation layers in ggplot2: https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org/reference/annotate.html.↩︎